|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Pinkhes-Dov Goldenshteyn’s enduring faith amidst suffering and loss

By: Yaakov Ort

Every author needs to have a primary audience in mind before setting out to write. The ultimate test of the effectiveness of the work, regardless of the genre, is whether or not the writing was an agency for change in the lives of his or her target readers. Whether the work is short or long, fiction or nonfiction, poetry or polemic; whether it is meant to educate or entertain, inform or inspire, or achieve some combination of all the above, the work must result in some kind of shift in readers’ feelings, knowledge or perspective to be deemed a success.

In the very first page of his autobiography, Pinkhes-Dov Goldenshteyn (1848-1930) tells us who his primary audience is and what he hopes to achieve.

I wrote this book for my children and relatives who are spread throughout numerous countries … I wanted them to be able to understand what their father endured during his lifetime and how G‑d always helped him and never abandoned him. I also want those who plagued and tormented me and are currently in Russia to read this in order to learn the moral lesson that there is a G‑d in the world who protects the harassed and oppressed and repays everyone according to his deeds.

May they repent.

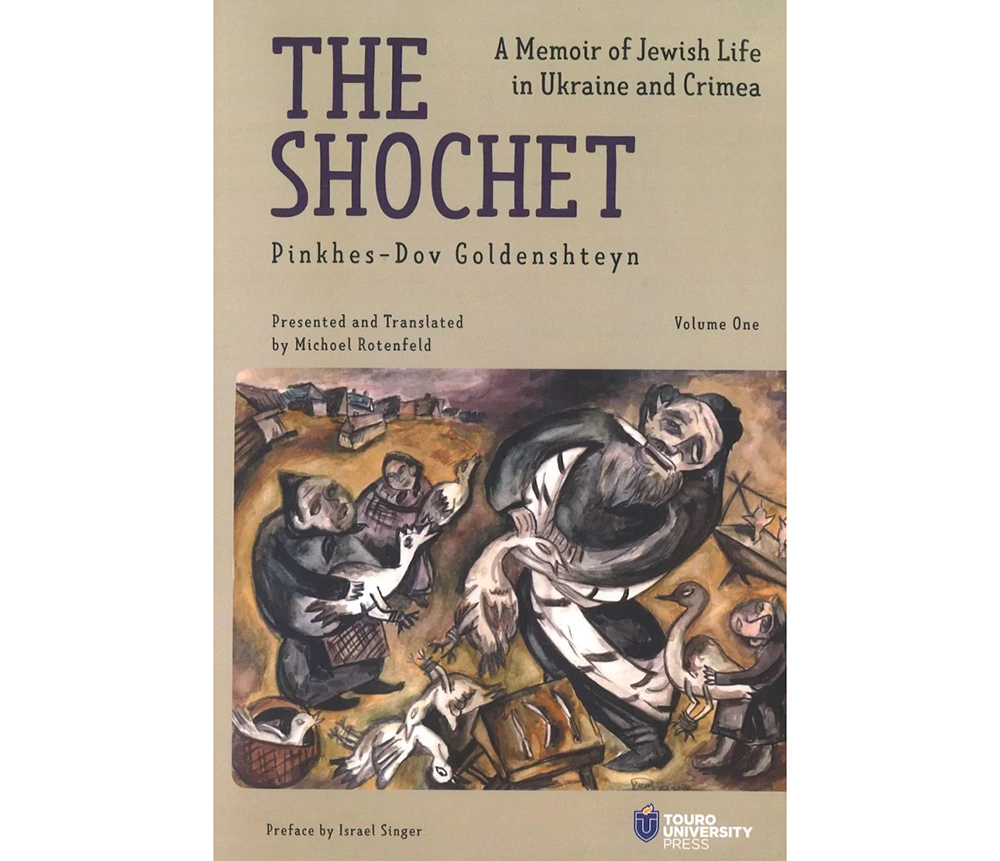

The Shochet—A Memoir of Jewish Life in Ukraine and Crimea— is an unparalleled autobiographical account of faith and piety amid poverty, suffering and loss experienced by a smart, rambunctious and traumatized orphan living in the fast-disappearing traditional Jewish communities in late 19th-century Eastern Europe. As a child, adolescent and even as a young adult, Goldenshteyn, known as Pinye-Ber, was tossed between a succession of families and communities that didn’t know how to handle him.

For the story of Goldenshteyn’s life to serve as a role model and inspiration for teshuvah—repentance—by his descendants and and his tormentors, the first requirement is for him to simply tell the truth about what he went through without embellishment or exaggeration, and he does that convincingly.

Thanks to Michoel Rotenfeld’s scholarly and deeply engaging translation—the memoir was originally written in Yiddish and published in the Land of Israel in 1928-29—and introduction, Goldenshteyn comes across as someone without guile or pretense, a person who has neither the desire to highlight the faults of others nor the need to hide his own shortcomings and mistakes.

But his life was not just any life. It is the life of the archetypal orphan who, almost a century after his passing, arouses feelings of love, protection and compassion.

His life was a heroic journey in which he finally found his identity far from home in the village of Lubavitch, in the ideology of Chabad and the courts of the third and fourth Chabad Rebbes, the Tzemach Tzedek and the Rebbe Maharash (Rabbi Shmuel of Lubavitch). He found his occupation as a shochet (a ritual slaughterer) and spent many of his adult years practicing his trade and raising a large Jewish family in Crimea, a place seen as a Jewish backwater and thus a center of assimilation that negatively impacted his own children’s Jewish observance. He then tried to find refuge in immigration to Ottoman-controlled Palestine before World War I, but his difficulties only increased, as did his trust and faith in G‑d.

A Tragic Childhood

Born in 1848 in Tiraspol in the Tsarist Russian province of Kherson—a part of historical Ukraine—Pinye-Ber was the youngest of eight siblings who were born to a poor, pious, loving Jewish family of Bersheder Chassidim, who instilled in their children a desire to above all to live a G‑dly life immersed in Torah and Chassidic traditions. But his mother died when he was 5 years old, his father passed away less than two years later, and the children found themselves living in abject poverty. As Pinye-Ber recalls:

The orphaned children all lived together in a tiny, little dwelling … Understandably their expenses could barely be met. More than once they did without food or drink to at least have money for heating so they would not freeze; but even so, there was not enough money for heating.

One by one, Pinye-Ber’s older siblings died, or settled for unhappy marriages and then died, leaving the young boy alone in the world. The succession of tragedies in his life is so remarkable that if this was a work of fiction, it would be proper to admonish the author: “Enough tragedy already. You’ve made your point.”

With no close relatives to care for him, the boy was taken into foster care by distant relatives—a wealthy, childless merchant called Reb Elye the Vinegar Maker, and his cruel, shrewish wife. As bad as it was at home, school was worse.

By nature I was happy; if I chuckled or simply had a happy expression on my face, I was given a blow of the strap across my face or back. It made no difference where the strap struck as long as it hit me well. I was never beaten on account of my learning, because I knew the sections of Talmud and khimesh with Rashi’s commentary as soon as I reviewed them once on Monday. So I was left with nothing to do all week except listen to the others constantly reviewing Sunday’s lessons and still not mastering them by Thursday. Naturally, I had to laugh at them. But since they were children of the well-to-do, I was slapped because they were blockheads. I was slapped so much that I became disgusted with the kheyder and melamed. If only things would have gone well at home, but things were no good there either.

Desperate to escape from school after a particularly severe beating from his teacher, Pinye-Ber leaped out the window and ran off to the cemetery where his parents were buried.

Here was where my sisters would come during difficult times of loneliness and hardship to cry out their hearts to our parents. Here I too had come to plead and cry for my parents to somehow help me and make my life easier. And I was then all of eight years old.

Although he was found after a short while and returned to his sisters’ home, the next two decades of Pinye-Ber’s life are highlighted by stories about his running away: running away from foster families who first gave him hope, fleeing yeshivahs where he briefly felt he could make his mark as a scholar, running away from promises of matrimony, and along with it, a comfortable income of a young scholar from a good family supported by his in-laws; even running away from a wife he loved and respected and children he adored for the sake of imagined material or spiritual benefits that he would find someplace other than where he was.

Each of these attempted escapes from the reality of his life provides rich details in the tableaus of time and place, as well as insights into the daily and religious lives of Jews and Jewish communities bound to tradition and oblivious to the tectonic shifts going on around them. – Chabad.org

(To Be Continued Next Week)