|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: Menachem Posner

- Our People Left Egypt After 200 Years of Slavery

Passover, the first Jewish holiday, celebrates our people’s miraculous exodus from Egypt. Led by Moses and Aaron, our ancestors witnessed G‑d bringing 10 plagues upon our Egyptian slavemasters before leaving for freedom. Before G‑d split the sea for his nascent nation, He said: “For the way you have seen Egypt is [only] today, [but] you shall no longer continue to see them for eternity.”1 Yet it took only several hundred years before some Israelites returned to the land of our oppression.

- Jews Returned Following the Assassination of Gedaliah

Following the destruction of the First Holy Temple, a small, humble Jewish community remained in the Holy Land, governed by Gedaliah ben Achikam. After Gedaliah and many other Jews were murdered at a Rosh Hashanah feast, the community was in tatters. Some migrated to Egypt, where they hoped to escape famine and war. The Prophet Jeremiah warned them not to go, but they went nonetheless. Even after they settled there, Jeremiah continued to castigate the people for leaving the Holy Land and for serving idols in Egypt.2

- There Was a Pseudo Temple in Second Temple Times

During the Second Temple period, around the time of the Chanukah story, when Egypt was the center of the Alexandrian Greek empire, it was home to a significant Jewish community.

Under the leadership of a priest named Chonyo (Onias), they even built a large temple, which they saw as a parallel to the Holy Temple in Jerusalem. Chonyo’s temple was not, however, sacred. In fact, the Mishnah states that any priest who served in Chonyo’s temple was not allowed to serve in Jerusalem, just like priests who served idols.3

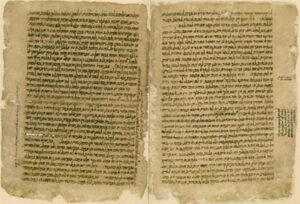

- They Translated the Torah Into Greek

By order of King Ptolemy, the Jews living in Egypt translated the Torah into Greek. The Sages say that day was as terrible for the People of Israel as the day that the Golden Calf was made, because the Torah was unable to be translated adequately.4

- They Had a Giant Synagogue

The Talmud describes an opulent synagogue in Alexandria, which could contain many thousands of worshippers, who sat according to profession. It was so large that it was impossible for everyone to hear the cantor. One person was thus designated to stand on the bimah (platform) in the center of the column-lined sanctuary and raise a handkerchief whenever it was time to say “amen.”

Tragically the entire congregation was killed—a punishment, the Talmud tells us, for resettling in Egypt.5

- Jerusalemites and Babylonians Lived Side by Side

In the post-Temple era, two great centers of Jewish scholarship arose—one in the Holy Land and the other in Babylon—each of which eventually produced a Talmud. In Egypt, there were representatives of both.

Cairo’s famous Ben Ezra synagogue was originally frequented by Jews who followed the (now defunct) Jerusalemite tradition. One feature of the Jerusalemite tradition is finishing the Torah over three years instead of an annual cycle.6 The globetrotting Rabbi Benjamin of Tudela (12th century) records that the Jerusalemites of Cairo had a longstanding tradition of joining together with the Babylonian Jews, who were completing the Torah on that day, for a joint prayer service.

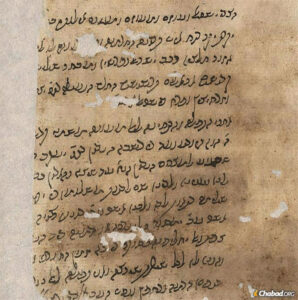

- Saadia Gaon Battled Karaites There

The great Rabbi Saadia Gaon was born in the Faiyum region in the late 9th century. As a young man, he perceived the threat to traditional Judaism posed by the Karaites, who rejected rabbinic teachings in favor of their own, original interpretations of Scripture. Saadia began his career as a staunch defender of Jewish tradition when he was just 23 years old. Soon after, persecution by the Karaites, including the ransacking of his home, forced him to leave Egypt for the Holy Land and then Babylon. He became known as one of the great leaders and teachers in Jewish history, who rendered the entire Torah into flowing Arabic, and whose teachings and traditions remain central to Judaism today.

- Maimonides Was Nagid

Moses Maimonides, the great Spanish-born philosopher, scholar, and leader, lived in Cairo, where he served as nagid (leader of the community) and personal physician to Sultan Saladin. Under his influence, Jewish observance was enhanced and Jewish precepts were taught in a way that many could appreciate and incorporate, including repentantf former Karaites.

- Most Egyptian Jews Today Are Sephardim

In the wake of the Catholic persecution of Jews in the Iberian Peninsula, which culminated with the Spanish expulsion of 1492 and the Portuguese expulsion of 1496, Spanish Jews (Sephardim) streamed into the relative tolerance of Muslim Arabia and North Africa, including Egypt.

- The Arizal Grew Up There

Rabbi Yitzchak Luria (1534-1572), known as the Arizal, was among the most celebrated Kabbalists. His father, Shlomo Luria, passed away when his son was eight years old, and the young boy was raised by his Sephardic maternal uncle, Rabbi Mordechai Francis of Alexandria. In Egypt, he studied under Rabbi Betzalel Ashkenazi, the author of the Shita Mikubetzet, and Spanish-born Rabbi David ibn Zimra, known as the RaDBaZ. Yet much of his learning was done alone, in solitude, on the banks of the Nile River.

- European Jews Came at the Turn of the 20th Century

With Europe becoming increasingly hostile to Jews, and the Suez Canal opening up many new business opportunities, European Jews, including Ashkenazim, joined the ranks of Egyptian Jews. The Ashkenazi community temporarily swelled during World War I, when the Ottomans expelled many Jews without Turkish citizenship from the Holy Land.

- Almost All Left in the Late 40s and 50s

As Zionist activity accelerated in Mandatory Palestine, things became increasingly difficult and dangerous for Jews in Egypt. Discriminatory laws were enacted, homes and synagogues were attacked, and life was unbearable. A significant portion of the community fled shortly after the Israeli War of Independence, in which Egypt fought against the Jewish forces. By the end of the 1950s, most Egyptian Jews had been expelled, and the once-great Jewish community of Egypt was a shadow of its former self. Today, there are less than a dozen officially recognized Jews living in Egypt. The synagogues have crumbled or become museums, the Jewish schools are devoid of Jewish children, and the 2,500-year-old Jewish community in Egypt has all but disappeared.

- There Are Egyptian Jews All Over the World

A significant portion of Egypt’s Jews immigrated to Israel, and many others scattered to Europe, North America, and South America, enriching Jewish communities with their unique traditions and culture.

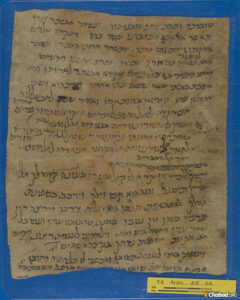

- They Observe ‘El Tawhid’ on the First of Nissan

On the first day of Nissan, two weeks before Passover when we celebrate the Exodus, Jews of Egyptian descent gather for Seder El Tawhid (“Unification”). This nighttime gathering includes reading from Torah and Psalms, as well as the recitation of El Tawhid, a Literary Arabic text that tells of the greatness of G‑d and His kindness to His people.

FOOTNOTES

- Exodus 14:13.

- This unfolds over several chapters, beginning with Jeremiah 40.

- Menachot 13:10.

- Masechet Soferim 1:7.

- Sukkah 51b.

- Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Tefilah 13:1.