Why the Left blames the attacks on White Supremacy

By: Danusha Goska

On Sunday, January 5, 2020, I was one of an estimated 25,000 protesters participating in the Solidarity March against antisemitism. Chilled and tightly packed marchers began in Manhattan’s Foley Square, stepped, painfully slowly, over the Brooklyn Bridge, and congregated in Cadman Plaza.

In Cadman Plaza, a protester held up a handmade sign reading “RACIST WHITE HOUSE.” Another man persistently walked in front of that man, carrying a mass-produced “Solidarity. No Hate No Fear” sign. The first man shifted position, but the second man would not be deterred. He clearly did not want Trump-blaming to triumph. The two protesters’ eventual shouting match typifies a national debate. How to understand recent attacks by blacks against Jews? Is it all Trump’s fault, or the fault of white supremacists? Or is there such a thing as black antisemitism?

That sign was just one of many attempts to attribute recent attacks on Jews by blacks in the New York City area to Donald Trump or white people in general. Democratic Michigan Congresswoman Rashida Tlaib blamed “white supremacists.” Tlaib is herself a Palestinian-American who has made inflammatory statements about Jews. Jewish Currents editor David Klion warned against “right-wing forces” “exploiting attacks” to “legitimize racism.” An invited speaker at Sunday’s rally said that racism was a problem for “the past three years,” that is, the years that Donald Trump has occupied the White House.

This article hopes to demonstrate that, contrary to leftist historical revisionism, headline-making incidents of black antisemitism stretch back decades. Though separated by time and space, these incidents share enough features to be understood as a cultural trend, rather than as the bad behavior of isolated lone wolves.

Naming and analyzing black antisemitism, contra David Klion, is not a “right-wing,” “racist” exercise. I’m Catholic and Polish-American and I have no problem calling out Catholic or Polish antisemitism. The folk motif of the blood libel, the derogatory Polish word “Zydokomuna,” the radio broadcasts of Catholic priest Charles Coughlin, are all part of my heritage. I explicitly reject them, condemn them, and distance myself from them. No, all African Americans are not antisemitic; only a minority are, but denunciation is all the more vital and urgent given persistent efforts to deny the very existence of black antisemitism, and to silence any discussion of it.

Van Wallach, a Times of Israel blogger, quotes antisemitic themes in African American writing dating back to 1965. A previous Front Page article mentioned the 1995 Freddy’s Fashion Mart protests that culminated in eight killings, the deadly 1991 Crown Heights pogrom, Khalid Abdul Muhammad’s 1993 speech at Kean College, and the 2002 Amiri Baraka poem that blamed Jews for the September 11, 2001, terror attacks.

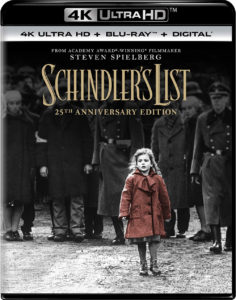

Here’s another incident. On January 17, 1994, Castlemont High School students went to the movies in Oakland, California. The movie was Schindler’s List. The students talked and laughed continuously throughout the film until, one hour into the showing, theater manager Allen Michaan stopped the projector. Audience members, “shaking with anger,” complained. “I’ve never seen such furious, hurt customers. Some were Holocaust survivors, and one woman was sobbing,” Michaan said. The students were asked to leave and their departure was applauded by the audience. A Castlemont student said that audience members applauding her departure was “so uncomfortable.” An NPR producer highlighted how victimized the students felt. “There was always a feeling of being policed or policing yourself if you’re young, brown, and carefree in a white space. That can harden you really quick.” Castlemont students’ behavior made national news.

Castlemont is a low-ranked, mostly black and Hispanic high school. Recent news stories describe it as a place of shootings, homelessness, manipulated test scores, and football protests featuring Colin Kaepernick himself.

Back in 1994, prominent persons said that African American students should not be criticized for laughing at Jewish suffering because African American students have very hard lives and are victims of oppression. When Schindler’s List producer and director Steven Spielberg visited the school, the Jerusalem Post reported on April 13, 1994, “About 100 students and others protested Spielberg’s appearance, saying the Holocaust does not speak directly to them.” “We don’t have any problem talking about their Holocaust. But there hasn’t been anything about the Asian holocaust, the Latino holocaust, the black holocaust,” said one Castlemont student. Another student said, “It was long ago and far away and about people we never met. We don’t know about those concentration camps, but I do hear a lot of Jew jokes.” Another student said, “We see death and violence in our community all the time. People cannot understand how numb we are toward violence.” And another, “I don’t want to hear anything about anybody else’s Holocaust before I hear my own.”

Those protesting Spielberg’s visit carried signs that said, “How can a Zionist Jew teach us about racism and oppression?” and “Zionist Jews are the new Nazis.” Before Spielberg took the mic, a student performed a monologue that began, “Dear Mr. President, I am a woman with three children and no food to eat.”

California’s Republican Governor, Pete Wilson, accompanied Spielberg. Wilson had previously said that welfare “seduces teenage girls into a life of poverty and encourages irresponsibility.” One student said to Wilson that she saw his visit “as an opportunity to vent the anger, and the spite, and the animosity I feel toward your entire time in office. I mean, I want to know was your main purpose in portraying yourself through the streets of my city where you have cut welfare, education, and many young futures, like mine” (sic).

A Castlemont teacher organized an “African Holocaust Day. There were musicians and African dancers, lectures on ancient Egypt and Jim Crow.” A speaker “wearing a regal brown and gold dashiki, a kufi, with a leather-bound neck pouch, walked up and down the front of a classroom, commanding students’ attention, pointing to placards listing the names of people who had been lynched … This is the Maafa … Maafa is another word for the African Holocaust.” One student’s takeaway from these presentations was the false impression that “Slave ships were owned by Jews.” A Jewish social worker at the school was asked, “Did your family own slaves?”

Film scholar Dennis Hanlon said that many students’ comments reflected their feeling that “their own history and suffering were largely ignored and that before they should be asked to understand another communities’ suffering, they should be allowed to learn more about their own.” Spielberg agreed, telling students that they were victims of bad press. Partly in reparations for these black students’ alleged victimization, Steven Spielberg made Amistad, about a slave uprising.

By 1997, the Washington Post published the false claim that “The only people who laughed during Schindler’s List were skinheads.” National Public Radio’s This American Life addressed the Castlemont incident in 2018. Times of Israel blogger James Inverne argued that This American Life’s handling of the topic perpetuated the notion that if Jews protest against antisemitism expressed by black people, they risk “creating more hatred towards Jews.”

A different event, thousands of miles away, echoes some of the same themes evident in the Castlemont incident. Those who insist that “black antisemitism” is a misnomer meant to distract attention from white racists, a recent invention, or that blacks who commit antisemitic acts are programmed to do so by white racists or Donald Trump might be surprised by a New York Times article entitled, “Jews Debating Black Antisemitism.”

“Confronted by racial and religious hatred … a shocked Jewish community is debating what to do about it,” the article begins. The article mentions suspicious synagogue fires in New York City. Some Jewish leaders quoted in the article argue for “vigorous” condemnation and counter action. Others fear that “defensive reaction might bring on a backlash and hasten the political antisemitism that all Jews seek to avoid.” Some argue that the Holocaust ended antisemitism. Others allege that anti-Jewish “incitement” gains momentum when religious, cultural and political leaders de not rapidly condemn it. When New York City’s mayor did speak out against antisemitism, a black teacher responded that the mayor was trying to “appease the powerful Jewish financiers of the city.”

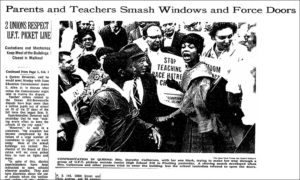

“Jews Debating Black Antisemitism” feels entirely of the moment. It reads as if it had been published in 2020. It wasn’t. The Times published this article on January 26, 1969, fifty-one years ago. The article is as if frozen in amber. The same debates are happening today, and there has been no resolution to them. “Jews Debating Black Antisemitism” concerns one of the most headline-grabbing outbreaks of allegations of black antisemitism. These allegations swirled around the 1968 Ocean Hill-Brownsville teachers’ strike.

Brownsville, a Brooklyn neighborhood, changed over decades from being predominantly Jewish to being increasingly black. Teachers were often Jewish. In the late sixties, African American activists demanded community control of schools. These activists were funded, ironically enough, by the Ford Foundation. This funding source for what would become an antisemitic manifestation is ironic because Henry Ford himself was a notorious anti-Semite. By 1968, Henry Ford had been dead for twenty-one years. His foundation, Heather MacDonald argues, had been radicalized into a steamroller of leftist social engineering. The Ford Foundation, MacDonald writes, exercised its considerable financial might to advance black separatists and anti-Semites. African American Civil Rights leader Bayard Rustin was critical of the black separatist position, but he didn’t have the heft of the Ford Foundation at his back.

Black activists terminated Jewish teachers. Albert Shanker lead teachers on what has been called the longest and largest teachers’ strike in US history. Shanker became so nationally prominent that his name was the punchline in a 1973 Woody Allen movie, Sleepers.

(Front Page Mag)

(To Be Continued Next Week)