Reviewed by: Prof. Bat-Ami Zucker, Bar-Ilan University.

(Originally published on H-Judaic, February 2020)

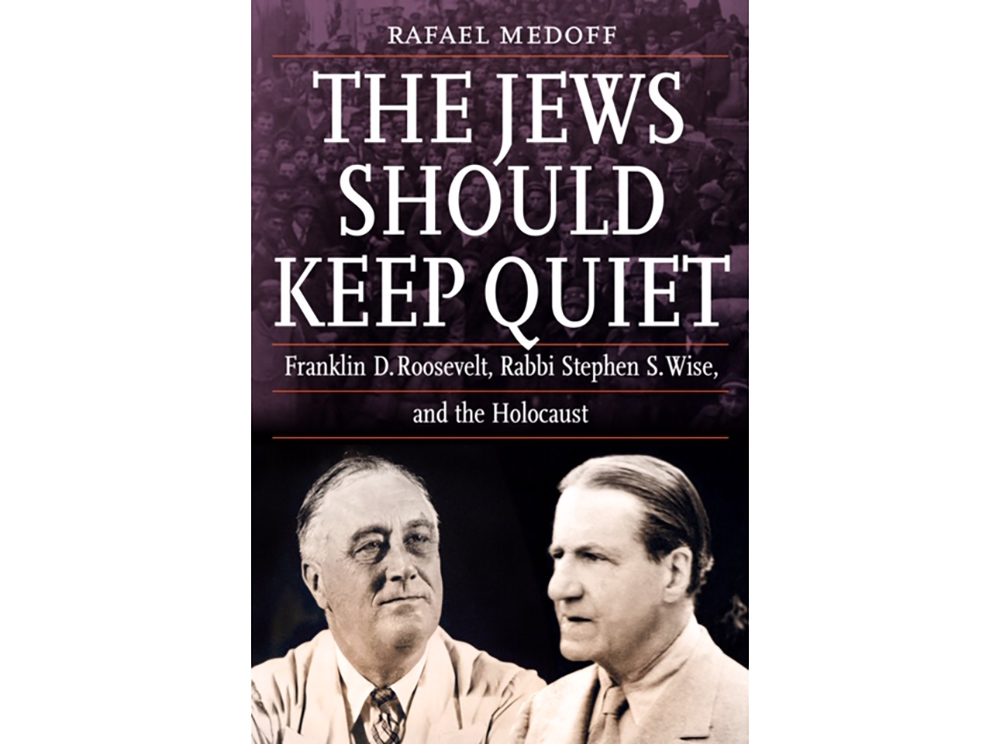

No American president enjoys being criticized. Still, it is troubling to realize the length to which Franklin D. Roosevelt—a president of presumably liberal sensibilities—went to prevent American Jewish leaders from challenging his policies toward European Jewish refugees during the Nazi era. Rafael Medoff’s The Jews Should Keep Quiet focuses on the relationship between President Roosevelt and Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, a relationship that FDR leveraged to suppress his Jewish critics. From Medoff’s portrayal, it is clear that Wise was dynamic, talented, and genuinely devoted to the Jewish community of which he was the foremost leader. However, he was also in poor health, stretched terribly thin, busy with simultaneously leading five Jewish organizations or institutions, and deeply resentful of anyone who seemed to threaten his status. Also—and perhaps most significant—Wise was a passionate supporter of FDR and the New Deal.

That was not an unusual position for an American Jewish leader. Yet it sometimes compromised Wise’s ability to represent the Jewish community in the halls of power. To be effective in Washington, the leader of an American ethnic minority group must be ready to work with, or against, either party, depending on the situation. This was Wise’s Achilles heel. He could not bring himself to challenge FDR. In the Wise correspondence, which Medoff mined in archives in New York City, Cincinnati, and Jerusalem, we find the rabbi describing President Roosevelt as “the All Highest” (p. 308), and the oval office as “General Headquarters” (p. 18).

Roosevelt exploited Wise’s devotion. The president granted him an occasional meeting—just enough to make Wise feel as if he had access to the chief executive. Unfortunately, “access did not equal influence” (p. 302), Medoff notes. Sometimes FDR called Wise by his first name and seemed to lend a sympathetic ear to the rabbi’s concerns. At other times, however, Roosevelt dropped the charm and bluntly warned Wise, directly or through intermediaries, that the Jews should keep quiet.

The president and his aides were especially concerned about the Emergency Committee to Save the Jewish People of Europe, better known as the Bergson Group. The group’s full-page newspaper advertisements and public rallies urging FDR to rescue European Jews annoyed and embarrassed the White House. Using documents that he secured under the Freedom of Information Act, Medoff shows how the FBI and IRS were utilized against Peter Bergson, spying on him in the hope of finding information that could be used to have him drafted or deported. (Bergson was a citizen of British Mandatory Palestine). At the same time, President Roosevelt repeatedly pressed Wise to take steps to suppress the Bergsonites. Wise managed to convince some VIPs to drop out of Bergson-sponsored events, persuaded at least one major news magazine to stop accepting Bergson’s ads, and even testified in Congress against a Bergson-sponsored resolution promoting rescue.

The Jews Should Keep Quiet describes how, at the very moment he was resisting calls from American Jews to rescue Jews from Europe, Roosevelt approved the creation of a US government commission to rescue medieval paintings and other treasured cultural artifacts in European battle zones. Medoff points to the irony of the administration saying it could not use even minimal military resources to save Jewish refugees, while at the same time sending US personnel into dangerous areas to save artwork. Evidence of that kind of perplexing double standard in US policy during the Holocaust surfaces repeatedly in this book and raises painful questions. Why rescue paintings—though important—but not people? Why bomb oil factories next to Auschwitz, but not the gas chambers or railways leading to them? Most of all, why turn away refugees when the immigration quotas were almost never full? Other historians have asked these questions but never really provided a satisfactory answer.

In pursuit of that answer, Medoff delves into FDR’s decision to intern Japanese Americans during World War II. Roosevelt’s private and sometimes public assertions about the Japanese being inherently untrustworthy and incapable of fully assimilating are surprisingly similar to numerous remarks that he made in private about Jews.

Roosevelt’s unpleasant comments about Jews are not well known. However, reliable sources, including the diaries of Treasury secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr. and vice president Henry Wallace and the private correspondence of members of Congress who met with the president, shed light on his views about Jews.

For example, FDR recommended “spreading the Jews thin” (p. 294) around the country so that they would not concentrate in any one area and dominate the economy or culture. Medoff compares this to a proposal by Roosevelt to disperse Japanese Americans around the country after they were released from internment. The similarity in Roosevelt’s attitude toward the two minority groups is chilling. It seems clear that FDR simply did not want too many Jews in America. Allowing the immigration quotas to be filled or taking steps to rescue refugees in Europe (and then perhaps having to take them in), did not accord with Roosevelt’s preference as to how the United States should look.

Rabbi Wise was aware of FDR’s private attitudes toward Jews. In one instance, Roosevelt remarked to Wise himself that antisemitism in Poland was the result of Jewish domination of the Polish economy. Yet Wise found himself unable to acknowledge the truth about his idol.

Medoff presents fascinating excerpts from the unpublished first draft of Wise’s autobiography in which the rabbi assessed FDR’s response to the Holocaust in terms that were far from flattering. However, that chapter never made it to the printer. The final, published version reflected only Wise’s unrelenting admiration for Roosevelt.

The Jews Should Keep Quiet is a chronicle of tragedy—of a cynical president and the conflicted and compromised Jewish leader whom he effectively manipulated. To his credit, Medoff avoids accusations and condemnations. His tone is measured; his prose is crisp. He simply lays out the facts, many of them previously unknown or misunderstood, about a disturbing but important chapter in American history. The Jews Should Keep Quiet takes a place in the top tier of studies of American responses to the Holocaust.

(Review of The Jews Should Keep Quiet: Franklin D. Roosevelt, Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, and the Holocaust, by Rafael Medoff. (Jewish Publication Society, 2019. 408 pp. $29.95)